Now go outside and look at the sky.

Astor House: Ceasefire for a Tiffin

Colonial Shanghai had always been a city of intrigue, chance and danger, a place where diplomats lunched beside spies and gunboats idled just offshore.

The Chinese government had been forced - essentially at gunpoint - to allow for the Concessions that made up the inner city of Shanghai, with large French and British Concessions south of Suzhou Creek, and the International Settlement - a conglomerate of US, German, Japanese, Russian and other countries' interests north of the Garden Bridge.

It was a free port with essentially no border controls for anyone arriving by ship, one of the most international places that anybody had ever seen, a grand whirlpool of trade, spycraft, politics and non-stop partying.

The city was a stop on many round-the-world cruises with it's metropolitan skyline an attractive sight as ships were arriving in dock along the Pujiang river.

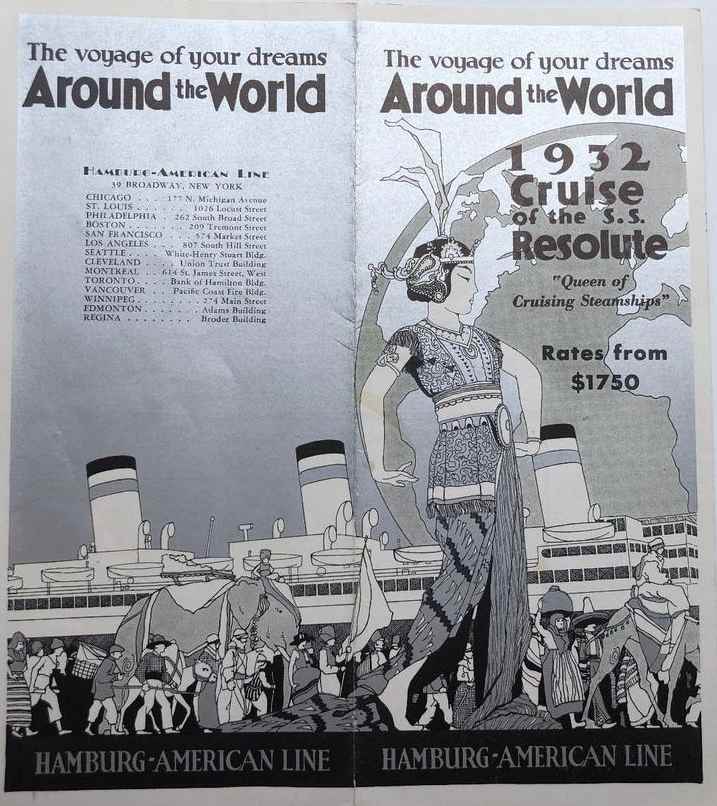

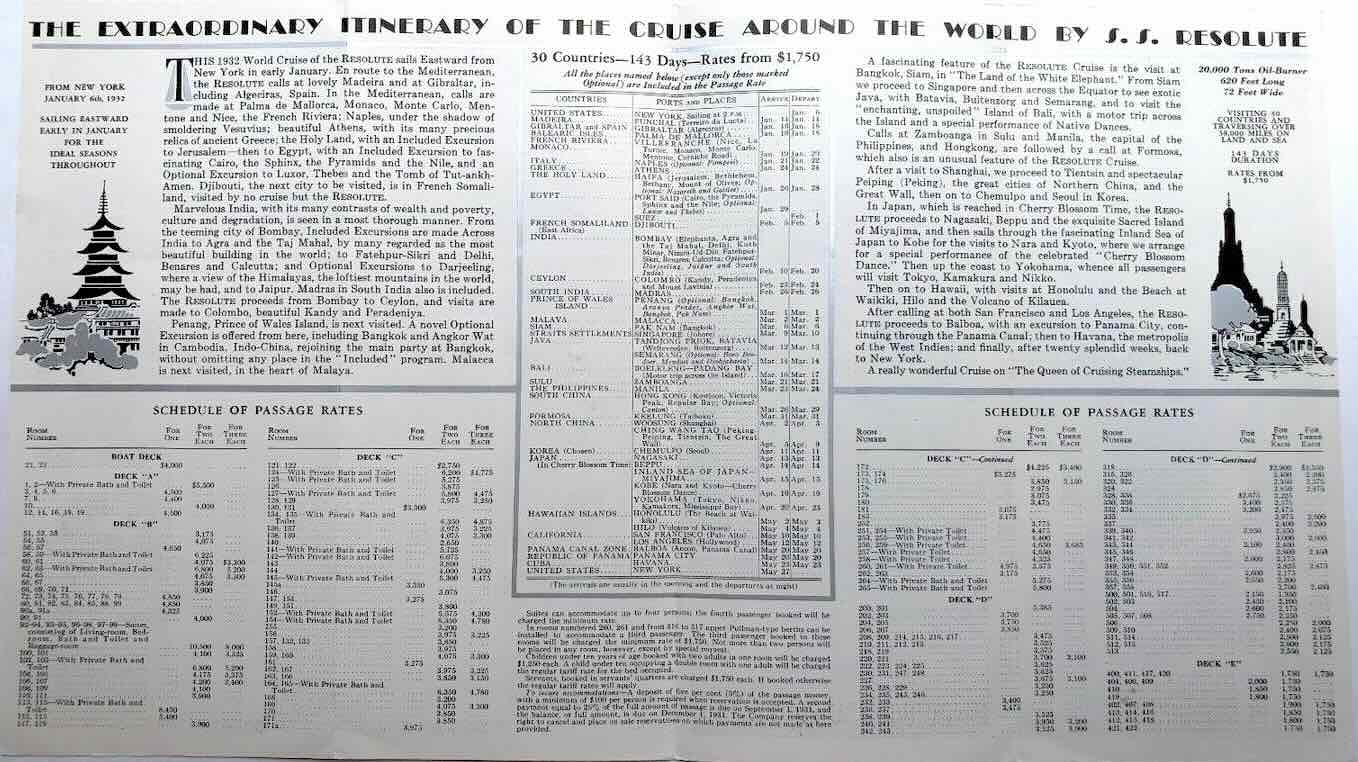

The passengers of the S.S. Resolute were hoping to see these sights as they embarked from New York on January 6th 1932 for a cruise around the world in 143 days.

The prices for this trip started at $1,750 per person in a two-bed cabin on Deck E. Inflation-adjusted this comes out to $40,000 per person in today's money. This in 1932, just three years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

We can imagine the passengers to be the usual Agatha-Christie-novel collection of characters. Heiresses of oil fortunes, European industrialists, mysterious relatives of various monarchs, German spies, Russian officers, Japanese scientists, the odd drunk writer. Maybe a Belgian detective on vacation.

As they were traveling through the Mediterranean, the Middle East and on to India, the situation in Shanghai was slowly getting complicated - much more complicated than it usually already was.

China had been in the throes of a multi-frontier civil war for more than a decade. There were enough shifting alliances to fill whole books:

The Japanese had invaded Manchuria and were fighting their way south. The Nationalist government under Chiang Kai Shek was fighting the Japanese, but also fighting the Chinese Communists. The Communists fought the Nationalists and the Japanese. Simultaneously, the Japanese fought the Russian Soviet armies in the north, as did the Nationalists. Warlords in central and eastern China, each with armies of tens of thousands, were occasionally supporting the Nationalists, or alternatively fighting each other, often ignoring or even helping the Communists.

That paragraph does not even begin to illustrate how insane the political situation was in China at this point.

Shanghai, as an international free port, stayed mostly out of the conflict, and it was generally able to defend itself as all the nations had troops stationed in town. But this delicate balance was not to last, as Japan sent more and more troops into China and into Shanghai.

Shanghai had a large Japanese community that was mostly living in the International Settlement, and there had been assassinations, bombings and general violence against Japanese troops with occasional fights involving local police forces as well as a wide array of Chinese Nationalist and Communist forces.

On January 28 1932, all of this came to a head in the Shanghai Incident. Over the next two months, Japanese troops, the Concession police forces and the Chinese 19th Route Army fought entrenched battles around the outskirts of Shanghai with street-by-street fighting across wide swaths of the International Settlement. Japanese bombs fell from airplanes all across the city.

By March 3rd a ceasefire took hold and as the fighting stopped, 7,000 soldiers had been killed and there were up to 10,000 civilan casualties.

Now in most other places, there would have been no way for a ship-full of tourists to show up in the middle of a fragile ceasefire in what was essentially a war zone. But this... this was Shanghai.

On April 2nd, the SS Resolute steamed into town early in the morning, passing at least three dozen Japanese battleships and also the war ships of many other nations.

The ship docked along the Pujiang near the Bund, the downtown waterfront, only a few hundred meters west of the Astor House Hotel. The hotel stood right at the end of the Garden Bridge in the International Settlement, which was swarming with 30,000 Japanese troops at that time. Many buildings in the area along the Suzhou Creek had been bombed or had received artillery strikes from Chinese cannons.

But life in the free port had to go on. There were no restrictions on travel for foreigners, so the passengers of the SS Resolute made their way to the famous Astor House Hotel by taxi, rickshaw, or a short stroll past the curio shops on Broadway.

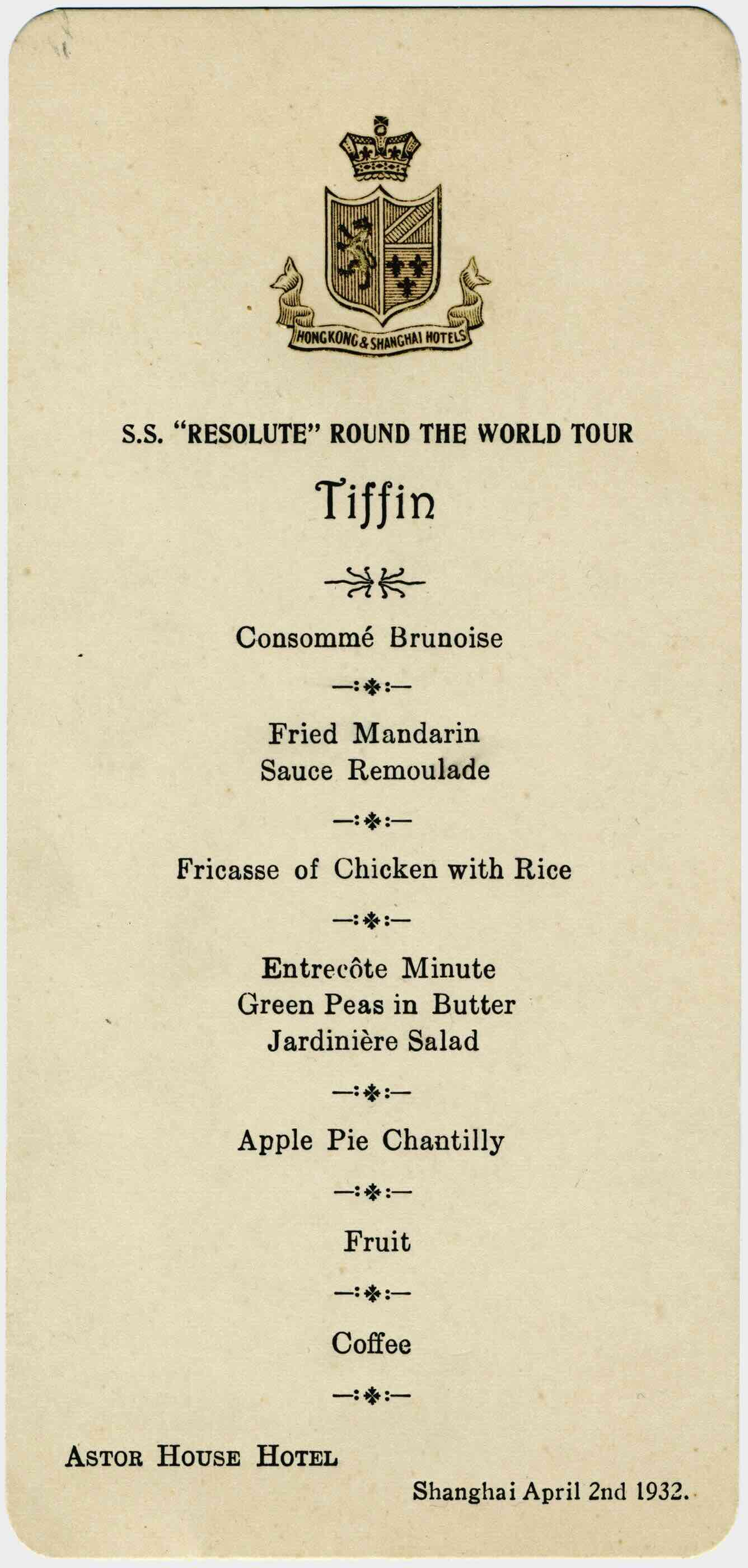

At the Astor House, a Tiffin - a light lunch - had been prepared for the passengers, and we have the menu for this memorable meal.

This card was printed in Shanghai for the Astor House and shows the seal of the Hongkong & Shanghai Hotels company, a legally British company that owned several prestigious hotels in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing. On some photos of this era the Astor House is seen flying the Union Jack.

The food is very definitely "international" and if any of the passengers were interested in the delights of Chinese food, they would have to strike out on their own for dinner to one of the many restaurants in the Concession area, allowing for the occasional fresh bomb damage in parts.

Speaking of the curio stores along Broadway, in our next post we are going to leave the Astor through its north-western exit in the new wing and stroll together with the passengers of the SS Resolute along Broadway.